There’s something very seductive about someone successful telling you how to live your life. But most life advice (or, Advice Porn), is pretty useless. That’s why I have a rule for myself for when I fall prey to Advice Porn’s clutches: close the tab.

But like all rules, there are exceptions, and one of them is this speech by Charlie Munger (Warren Buffett’s partner). It’s about “universal, can’t fail ideas” to live a successful life, and it’s truly great. This post is my curated cheat sheet.

I put this together so that whenever I’m reading the same old advice about what so-and-so said about living a good life, I can close the tab and come back to these 13 ideas. Hopefully it will serve the same purpose for you.

FOUNDATIONS

-

Be a learning machine

-

Understand the big ideas

-

Sit on your ass until you do it

MENTAL TRICKS FOR SOLVING PROBLEMS

AND AVOIDING BIG ERRORS

-

Invert

-

Write checklists

-

Play your best players

THINGS TO AVOID

-

Extreme ideas

-

Self-pity

-

Perverse incentives

-

Working for a boss you don’t admire

OUTLOOK ON LIFE

-

Expect adversity

-

Maximize for a web of seamless trust

-

Deserve what you want

FOUNDATIONS

1. Be a learning machine

Charlie starts the speech by telling us to get in the habit of always learning:

I constantly see people rise in life who are not the smartest, sometimes not even the most diligent. But they are learning machines. They go to bed every night a little wiser than they were that morning.

It’s not just that being a continuous learner is beneficial to you. Instead think of the acquisition of wisdom as a “moral duty.” That comes straight from Confucius, so according to the Lindy effect, this piece of advice is gonna last a while longer.

If your memory is terrible, you’re in luck, because becoming a learning machine doesn’t mean memorizing facts:

I frequently tell the apocryphal story about how Max Planck, after he won the Nobel Prize, went around Germany giving a same standard lecture on the new quantum mechanics. Over time, his chauffeur memorized the lecture and said, ‘Would you mind, Professor Planck, because it’s so boring to stay in our routine, if I gave the lecture in Munich and you just sat in front wearing my chauffeurs hat?’ Plank said, ‘Why not?’ And the chauffeur got up and gave this long lecture on quantum mechanics. After which a physics professor stood up and asked a perfectly ghastly question. The speaker said, ‘Well I’m surprised that in an advanced city like Munich I get such an elementary question. I’m going to ask my chauffeur to reply.’

The point of this story it that there are two kinds of knowledge: “chauffeur knowledge” and “Plank knowledge,” and from the outside they may look dangerously identical. But as Feynman said: there is a big difference between truly knowing something and knowing the name of something.

Also, if you’re going to be good at something, you need to be really interested in it. So pick stuff to learn that you’re really interested in! If you think you don’t have time or energy, pick things to learn that you’re truly interested in and your time and energy problems will be solved. Our cat is dumb enough to be scared by a vacuum cleaner but knows when it’s exactly 5:59pm and the automatic feeder is about to drop his food, a subject that greatly interests him.

Becoming a learning machine doesn’t take innate genius or superhuman willpower. It just takes curiosity. Here’s Walter Isaacson take on Leonardo da Vinci’s genius:

Yes, he was a genius: wildly imaginative, passionately curious, and creative across multiple disciplines. But we should be wary of that word. Slapping the “genius” label on Leonardo oddly minimizes him… In fact, Leonardo’s genius was a human one, wrought by his own will and ambition. It did not come being the divine recipient, like Newton or Einstein, of a mind with so much processing power that were mortals cannot fathom it. Leonard had almost no schooling and could barely read Latin or do long division. His genius was of the type we an understand, even take lessons from. It was based on skills we can aspire to improve in ourselves, such as curiosity and intense observation.

- Walter Isaacson, Leonardo da Vinci

So, if curiosity and imagination are enough for Leonardo, they’re good enough for you. Become a #LearningMachine.

2. Understand the big ideas

Okay, now that we’re on the subject of learning, you need to have a solid grasp of everything you missed out on by not having a core curriculum. That means learning the “big ideas in the big disciplines:”

The really big ideas carry about 95% of the freight, [and so] it wasn’t at all hard for me to pick up about 95% of what I needed from all the disciplines and to include use of this knowledge as a standard part of my mental routines.

What are these “big ideas?” He mentions in other speeches that they are, at the minimum:

-

Engineering: the redundancy/backup system model

-

Mathematics: the compound interest model

-

Physics: Breakpoint/tipping-moment/autocatalysis model

-

Biology: Darwinian synthesis model

-

Psychology: cognitive biases

-

Economics: opportunity cost, incentives, tragedy of the commons model

Of course, Charlie suggests learning these ideas yourself. “To this day, I have never taken any course, anywhere, in chemistry, economics, psychology, or business.” Buy some textbooks, read some blogs, watch some YouTube videos. Then, once you learn them, you have to practice them, because like a “concert pianist, if you don’t practice you can’t perform well.”

One of the main benefits you get from learning the big ideas is avoiding “man with a hammer syndrome.” If you have a lot of skills over many disciplines, you’ll be carrying multiple tools.

You have to learn many things in such a way they’re in a mental latticework in your head and you automatically use them the rest of your life. If you many of you try that, I solemnly promise that one day most of you will correctly come to think ‘Somehow I’ve becomes one of the most effective people in my whole age cohort.’ And in contrast, if no effort is made toward such multidisciplinary, many of the brightest of you who choose this course will live in the middle ranks, or in the shallows.

3. Be assiduous

“Sit on your ass until you do it.”

MENTAL TRICKS FOR SOLVING PROBLEMS AND AVOIDING BIG ERRORS

4. Invert, or learn where you’re going to die, so you don’t go there

This is the most famous Mungerism. Another way of putting it: invert your problems, and they become easier to solve.

The way complex adaptive systems work, and the way mental constructs work, problems frequently become easier to solve through inversion. If you turn problems around into reverse, you often think better.

Instead of thinking “how can I succeed in life?” think “how can I fail?” Think about how you can avoid the worst situations and don’t follow that path, and you’ll end up just fine.

Another way to put it:

“It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid.”

5. Write checklists

Despite years of experience and thousands of reps, pilots still use checklists to take off. Routine procedures are always accompanied by a checklist in the cockpit, and they work great at reducing errors. So what makes you think you can avoid mistakes without them?

Charlie suggests creating a series of checklists for common “mental routines” that going through them whenever you are thinking through a problem. He doesn’t go into much detail about what they should consist of, but I could find references in other talks to these two:

Ultra-Simple, General Problem-Solving

-

Decide the big “no brainer” questions first

-

Apply numerical fluency (make things quantitative)

-

Invert (see Idea #4, above)

-

Apply multidisciplinary ideas (see Idea #3, above)

-

Watch out for a combination of 2nd and 3rd order effects

The Two Track Analysis

-

What are the factors that govern the interests involved, rationally considered?

-

Where the the subconscious influences, where the brain is automatically forming conclusions? (Influences from instincts, emotions, cravings, etc)

Psychological biases

- Charlie has 25 of these that he writes down in another essay

Bonus quote, from Atul Gawande’s The Checklist Manifesto:

A five-point checklist implemented in 2001 virtually eradicated central line infections in the intensive care unit at Johns Hopkins Hospital, preventing an estimated 43 infections and eight deaths over 27 months. Gawande notes that when it was later tested in I.C.U.’s in Michigan, the checklist decreased infections by 66 percent within three months and probably saved more than 1,500 lives within a year and a half.

6. Play your best players

This one was surprising to me. Charlie suggests ”maximizing non-egality,” which definitely goes against my liberal arts education. Instead of letting everyone take a turn, he argues that “the game of competitive life often requires maximizing the experience of the people who have the most aptitude and the most determination as learning machines.”

“And if you want the very highest reaches of human achievement, that’s where you have to go. You do not want to choose a brain surgeon for your child by drawing straws to select one of fifty applicants… You don’t want your airplanes designed in too egalitarian a fashion. You don’t want your Berkshire Hathaways run that way either. You want to provide a lot of playing time for your best players.”

THINGS TO AVOID

7. Avoid extreme ideology

Another thing to avoid is extremely intense ideology because it cabbages up one’s mind. You see a lot of it in the worst of the TV preachers. They have different, intense, inconsistent ideas about technical theology, and a lot of them have minds reduced to cabbage.

Charlie warns that this can happen with political ideology too.

When you announce that you’re a loyal member of some cult-like group and you start shouting out the orthodox ideology, what you’re doing is pounding it in, pounding it in, pounding it in. You’re ruining your mind, sometimes with startling speed.

Of course, the difficulty is that no one feels that _their_ ideology is “extreme,” which makes this a tough one to introspect. There are many things that are important and right yet unconventional, which naturally seems “extreme” to certain people. So how do you avoid this problem? Charlie suggests an “iron prescription:”

I feel that I’m not entitled to have an opinion unless I can state the arguments against my position better than people who are in opposition. I think I am qualified to speak only when I’ve reached that state.

8. Avoid self-pity

I had a friend who carried a thick stack of linen-based cards. And when somebody would make a comment that reflected self-pity, he would slowly and portentously pull out his huge stack of cards, and take the top one and hand it to the person. The card said, ‘Your story has touched my heard. Never have I heard of anyone with as many misfortunes as you.’…

Every time you find you’re drifting into self-pity, whatever the cause, even if your child is dying of cancer [this isn’t just hypothetical; Charlie’s first son died from leukemia], self-pity is not going to help. Just give yourself one of my friend’s cards.

9. Avoid perverse incentives

Even if you think you know about the power of incentives, you’re probably still underestimating them.

Never a year passes but I get some surprise that pushes a little further my appreciation of incentive super-power…Never, ever, think about something else when you should be thinking about the power of incentives.

Incentives can be used for good:

One of my favorite stories about the power of incentives is the Federal Express case. The integrity of the Federal Express system requires that all packages be shifted rapidly among airplanes in one central airport for each night. But things moved too slowly, and packages were not delivered, or arrived damaged… Somebody got the happy thought that it was foolish to pay the night shift by the hour when what the employer wanted was not maximized billable hours of employee service… Maybe, this person thought, if they paid the employees per shift and let all night shift employees go home when all the the planes were loaded, the system would work better. And, lo and behold, that solution worked.

But even more easily, they can backfire, leading to a “perverse incentive.” There’s a great list on wikipedia of perverse incentives, like:

The 20th-century paleontologist G. H. R. von Koenigswald used to pay Javanese locals for each fragment of hominin skull that they produced. He later discovered that the people had been breaking up whole skulls into smaller pieces to maximise their payments.

So, avoid situations where you are in a perverse incentive structure, because it’s really hard to avoid their influence. A common one some of my friends are facing is law firm billable hour quotas. Charlie’s advice for that?

One of the things you’re going to find in at least a few modern law firms is high billable-hour quotas. I could not have lived under billable-hour quotes… I don’t have a solution for the situation some of you will face. You’ll have to figure out for yourselves how to handle such significant problems.

To my lawyer friends: good luck, I guess…

10. Avoid working for someone you don’t admire

You particularly want to avoid working directly under somebody you don’t admire and don’t want to be like. It’s dangerous. We’re all subject to control to some extent by authority figures, particularly authority figures who are rewarding us… Generally, your outcome in life will be more satisfactory if you work under people you correctly admire.

I like how he adds the “correctly” here.

OUTLOOK ON LIFE

11. Expect terrible things to happen

Warning: terrible things will inevitably happen in life. But we have a choice as to how we react to those terrible things.

Another thing, of course, is life will have terrible blows, horrible blows, unfair blows. Doesn’t matter. And some people recover and others don’t. And there I think the attitude of Epictetus is the best. He thought that every mischance in life was an opportunity to behave well. Every mischance in life was an opportunity to learn something and your duty was not to be submerged in self-pity, but to utilize the terrible blow in a constructive fashion. That is a very good idea.

This lines up well with the theory of “post traumatic growth” that I came across in Jonathan Haidt’s _The Happiness Hypothesis._ That book (which I highly recommend) has a chapter on the silver lining of adversity. Here’s an excerpt from the book:

When tragedy strikes, however, it knocks you off the treadmill and forces a decision: Hop back on and return to business as usual, or try something else? There is a window of time—just a few weeks or months after tragedy—during which you are more open to something else… Adversity may be necessary for growth because it forces you to stop speeding along the road of life, allowing you to notice the paths that were branching off all along, and to think about where you really want to end up.

Traumas often shatters belief systems and robs people of their sense of meaning. In so doing, it faces people to put the pieces back together… London and Chicago seized the opportunities provided by their great fires to remake themselves into grander and more coherent cities. People sometimes seize such opportunities, too, rebuilding beautifully those parts of their lives and life stories that they could never have torn down voluntarily.

So, yes, it’s a bit depressing to expect terrible things to happen. But at least there is a silver lining, in that adversity can lead to great opportunities to rebuild and reassess. Charlie lets that sink in with this Houseman poem:

The thoughts of others Were light and fleeting, Of lovers’ meeting Or luck and fame. Mine were of trouble, and mine were steady, And I was ready When trouble came.

12. Maximize a web of deserved trust

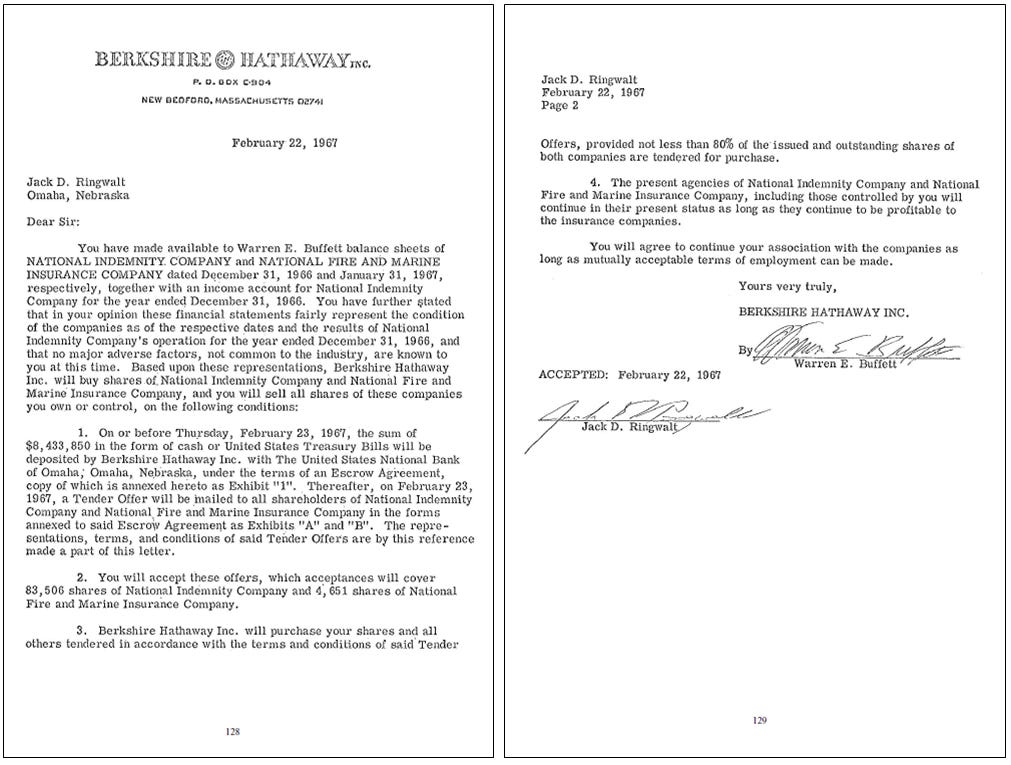

The 1.5 page contract Buffett used to buy National Indemnity in 1967. For comparison, the Twitter merger agreement is 73 pages. And that didn’t work out so well.

Be trustworthy and dependable, and you’ll probably get what you deserve, which is friends that are trustworthy and dependable. This is what Charlie calls this the highest form that civilization can reach, or a seamless web of trust. Seamless trust means you can bypass bureaucracy and procedure and “mumbo-jumbo,” which obviously no one likes. Living and acting this way also helps avoid long, stupid, public legal battles.

One other piece of advice: “if your proposed marriage contract has 47 pages, my suggestion is that you not enter.”

13. The safest way to get what you want is to deserve what you want.

This is my favorite one. In classic Charlie fashion, he gives us an insight so intuitive and clear that I can’t believe I’d never heard it before. It’s also empowering, because while getting what you want is often uncontrollable, being someone who ”deserves what you want” is always achievable.

In case it didn’t stick, he (of course) gives us a capitalism-flavored version of the same idea: “you want to deliver to the world what you would buy if you were on the other end.” He goes on:

There is no ethos in my opinion that is better for any lawyer or any other person to have. By and large, the people who’ve had this ethos win in life, and they don’t win just money and honors. They win the respect, the deserved trust of the people they deal with. And there is huge pleasure in life to be obtained from getting deserved trust.

There are two important caveats to this idea. The first is that “deserving” what you want definitely does not mean you will get what you want. Many people in this world have deserved to be rich and famous but are not because of structural societal issues, or just plain bad luck. While deserving what you want is the _safest_ way to get what you want, but it is by no means guaranteed.

Second, you could get lucky and become rich and famous by being an asshole. But it won’t be a secret. People who die rich and famous and didn’t deserve it end up with a funeral where most of the people there are to celebrate the fact that you’re dead, and you probably don’t want that.

That reminds me of the story of the time when one of these people died, and the Minister said, ‘It’s now time to say something nice about the deceased.’ And nobody came forward, and nobody came forward, and nobody came forward, and nobody came forward. And finally one man came up and said, ‘Well, his brother was worse.’…

A life ending in such a funeral is not the life you want to have.

So, remember: while never guaranteed, the absolute safest way to get what you want is to deserve it.

The End

And there you have it. From one Charlie to another, that’s thirteen universal, can’t fail ideas about how to life a successful life. A reminder to myself: Next time you catch yourself reading that Advice Porn, come back here.

Well, that’s enough for one graduation. I hope these ruminations of an old man are useful to you. In the end, I’m like the Old Valiant-for-Truth in The Pilgrim’s Progress: “My sword I leave to him who can wear it.”

FOUNDATIONS

-

Be a learning machine

-

Understand the big ideas

-

Sit on your ass until you do it

MENTAL TRICKS FOR SOLVING PROBLEMS

AND AVOIDING BIG ERRORS

-

Invert

-

Write checklists

-

Play your best players

THINGS TO AVOID

-

Extreme ideas

-

Self-pity

-

Perverse incentives

-

Working for a boss you don’t admire

OUTLOOK ON LIFE

-

Expect adversity

-

Maximize for a web of seamless trust

-

Deserve what you want

Thanks to Gilad, Jason and Sask for editing and feedback!